The Shining is a bit of an oddity in Stanley Kubrick’s career for a number of reasons, one major one being that his initial motivation for making it was because he wanted a commercial hit. Choosing a Stephen King novel feels a bit weird, too; as awesome as he is, he’s in a slightly different category from people like Thackeray, Burgess, and Nabokov, the last three authors whose novels Kubrick adapted, and Schnitzler, to whom Kubrick would turn later.

And, while the resulting movie ended up being terrifically enjoyable, with Kubrick’s customarily meticulous craft and one of the all-time great Jack Nicholson experiences, The Shining is one of the only movies Kubrick ever made where one has to determine whether the elements that don’t immediately add up are due to mistakes. This is not to say that they are, by any means, but there are enough of them, and so many of them could easily be the result of on-the-fly revisions—Kubrick was writing new script pages on set so frequently that Jack and Shelley Duvall often had to learn the scene they were about to do immediately before filming—that one wonders.

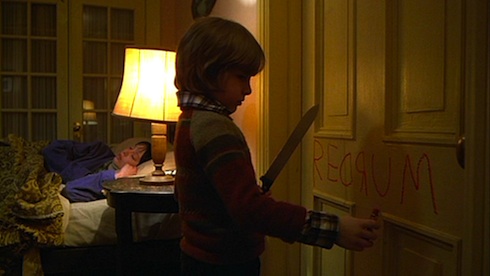

Despite that, The Shining still weirdly succeeds almost perfectly in being what it set out to be: a pop commercial movie, albeit one directed by someone for whom making that kind of movie is learned rather than natural behavior. It’s a movie made up of a series of set pieces and brilliant moments more than a coherent story, but a series of set pieces and moments what a commercial movie is, now even more than then. Why is Jack Nicholson flipping out? Irrelevant, he’s awesome. Why’s the kid so creepy, and why’s he need the artifice of his imaginary friend to be psychic? Doesn’t matter, that “redrum” business is tops. And why does Shelley Duvall look like she’s about to pass out from the flu? Well, that’s because principal photography went on for a year (two or three months is usually considered enough time to even waste some) and her relationship with Kubrick was so tense that she was drop-dead sick for eight months. But never mind that.

As a pop, big-budget horror movie, The Shining has everything one could want. There’s the big creepy hotel (whose elevators bleed), lots of ghosts, as technically gifted a director as ever called “action” using every lighting, compositional, and editing trick at his disposal to freak us out, and a score full of shrieking, atonal avant-garde string, and synthesizer music. Kubrick takes his time doling out the scares as well, letting the tension build over a long (nearly two and a half hours) running time, and never going for cheap shocks. Even his decision to jettison nearly all of the parts in the book where Stephen King explained what was going on works for the movie, even if it makes it more Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining than King’s (which, it barely even needs to be pointed out, was the idea). Not knowing what’s going on in any easily decipherable way helps the movie be as disconcerting and genuinely frightening as it is. Nothing is scarier than the unknown.

Tied directly to the movie’s gradual build is the room Kubrick gives his cast to strut their stuff. With the exception of Shelley Duvall (who was sick, and constantly being browbeaten by the director) and the kid (who was a kid), the cast is extraordinary. (In other words, “yeah, two of the three people who get 90% of the screen time are problematic, but everybody else is awesome“; I know that’s kind of a weird backhanded compliment.) Best among them all are Scatman Crothers as the hotel’s chef and the only other person we meet with extrasensory powers, about whose performance all my cinema theory background and acting training just flies out the window, and all I can do is geek out about how great he is. All you can do is love the guy. His warmth and goodness pervades everything, even if he ultimately errs in not telling the kid why he shouldn’t go into room 237 (but that’s the script’s problem, not his). But there are also Joe Turkel, as the “bartender” and Philip Stone as the clumsy “Delbert Grady,” both of whom are magnificent in different ways, Turkel in that he’s the chummiest upscale bartender to ever exist (even though he doesn’t) and Stone in that he builds, much like the movie itself, slowly to a demonic, quite scary peak.

And, of course, there’s Jack Nicholson. If one is in a particularly “Santa isn’t real” sort of mood, one can make the case that technically, Jack’s a little shaky as an actor at times. Which is, technically, true. But his greatest heights make the occasional missteps worth it, mostly because Jack is a movie star among movie stars. Movie stars can actually have a negative impact on some movies, because the gravitational pull of their charisma throws the rest of the movie off its axis, but in The Shining, this isn’t a problem, because Jack ends up being the bad guy (a subtle but significant change from the book, where he’s an agent of evil, not a source thereof) and any horror movie worth its salt needs a good, scary bad guy. Jack’s complete lack of subtlety ends up being a great asset to the movie, as he pulls out all the stops; even if he does so almost from the beginning of the movie, it’s still okay, because when it’s time to be scary, he’s scary.

Which is why The Shining works. Kubrick may have made a strange, dark, long pop movie, but he made a damned good one. It’s considerably more fun to experience than deconstruct, and while at times frustratingly inscrutable to fans of the book (not to mention that book’s author), still an enormously effective horror picture and one of the best examples on record of how to make radical and even fundamental changes to source material and still create a successful adaptation.

There’s also the matter, in less intellectually rigorous terms, of The Shining being awesome. Which it is. I could have merely left it at that, but why it’s awesome is important, too.

Danny Bowes is a playwright, filmmaker and blogger. He is also a contributor to nytheatre.com and Premiere.com.